【eroticism in horror】

Working on eroticism in horrorMy Novel

Books

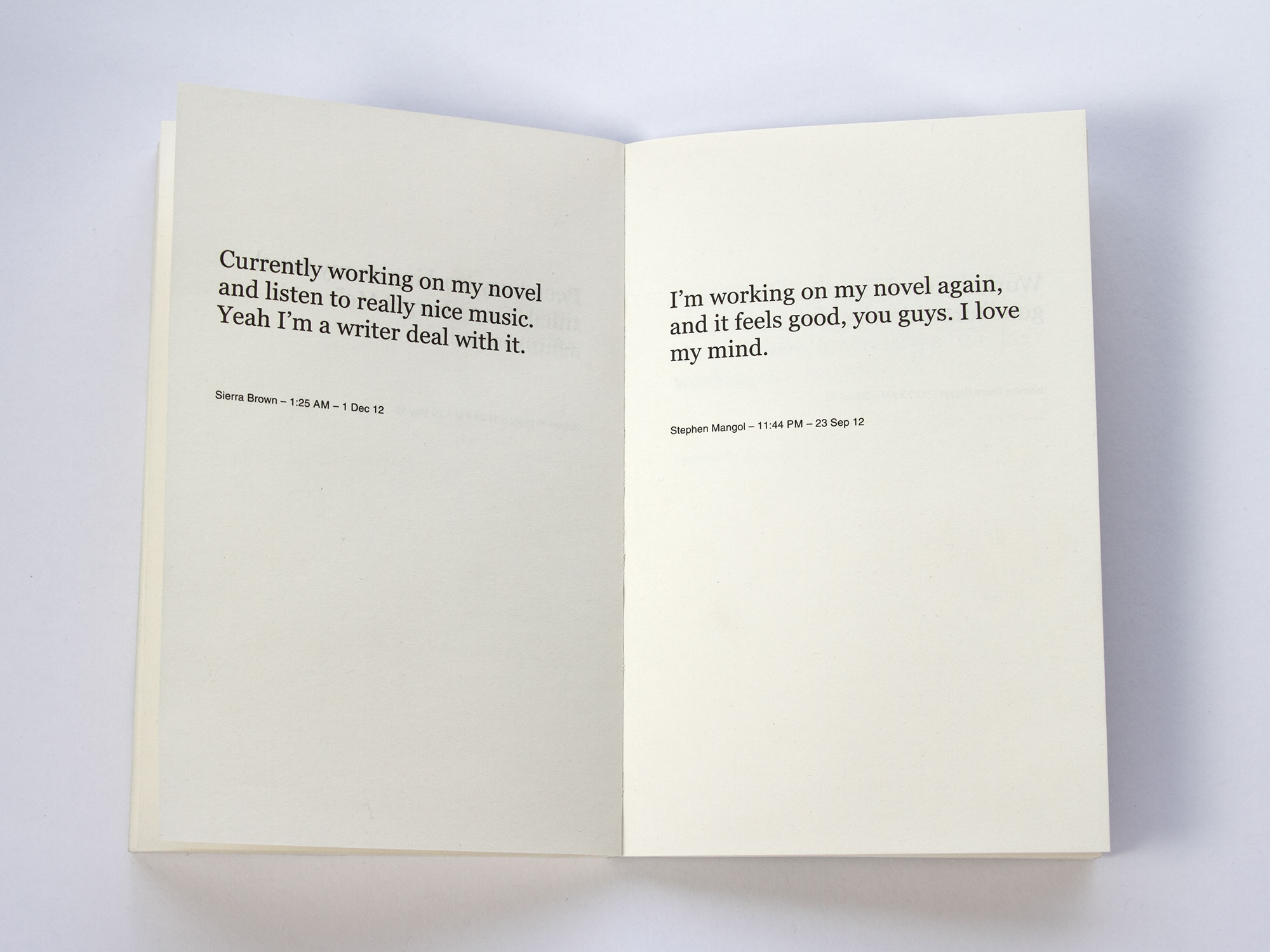

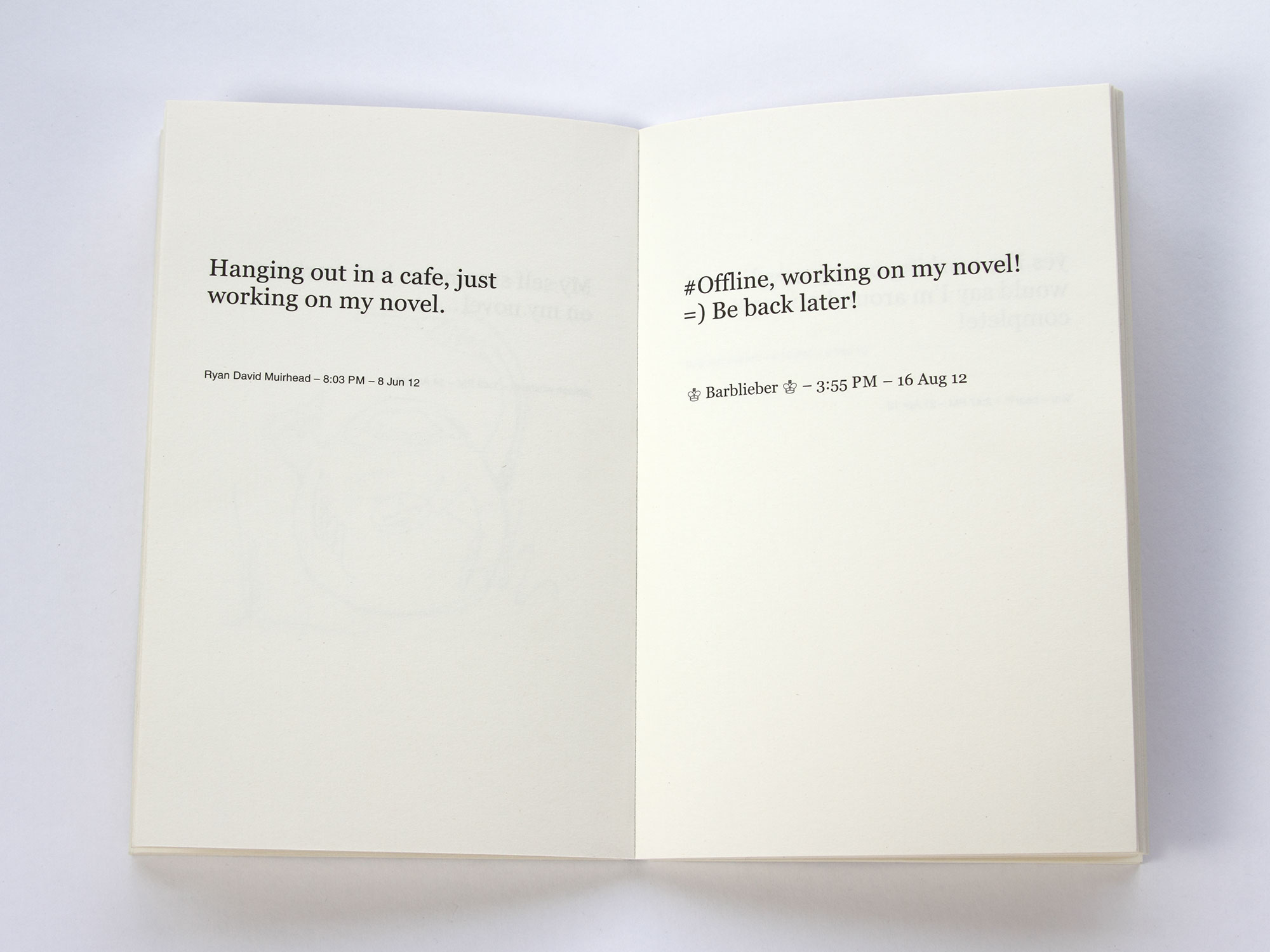

From Cory Arcangel’s Working on My Novel.

I wonder whether there will ever be enough tranquility under modern circumstances to allow our contemporary Wordsworth to recollect anything. I feel that art has something to do with the achievement of stillness in the midst of chaos. A stillness that characterizes prayer, too, and the eye of the storm. I think that art has something to do with an arrest of attention in the midst of distraction. —Saul Bellow, the Art of Fiction No. 37, 1966

Cory Arcangel’s new book, Working on My Novel—based on the Twitter feed of the same name—is a compilation of tweets from people who are putatively at work on novels. No more, no less. On Twitter, this concept feels merely clever; printed and bound as a novel would be, though, it becomes a vexed look at novels’ position in the culture, and a sad monument to distraction. Or so it seems to me. Arcangel’s “elevator pitch” puts a brighter gloss on it:

Working on My Novelis about the act of creation and the gap between the different ways we express ourselves today. Exploring the extremes of making art, from satisfaction and even euphoria to those days or nights when nothing will come, it’s the story of what it means to be a creative person, and why we keep on trying.

But the book piques my interest for the opposite reason: it’s the story of what it means to live in a cultural climate that stifles almost every creative impulse, and why it so often seems we should stop trying. Arcangel suggests there’s something inherently ennobling in trying to write, but his book is an aggregate of delusion, narcissism, procrastination, boredom, self-congratulation, confusion—every stumbling block, in other words, between here and art. Workingcaptures the worrisome extent to which creative writing has been synonymized with therapy; nearly everyone quoted in it pursues novel writing as a kind of exercise regimen. (“I love my mind,” writes one aspirant novelist, as if he’s just done fifty reps with it and is admiring it all engorged with blood.)

It’s also a comment on the peculiar primacy the novel continues to enjoy—not as an artistic mode but as a kind of elevated diary, a form of what we insidiously refer to as “self-expression,” as if anyone’s self is static enough to survive transmission to the page. Not for nothing do we have Working on My Novelinstead of Working on My Screenplay or Working on My Scrimshaw, because the novel, with its rich intellectual-emotional tradition and its (very occasional) commercial viability, is still perceived as the ideal vehicle for saying something ambitious. Even as fewer people read novels, we’re made to feel that writing one is a worthy, rigorous enterprise for serious thinking people, a means of proving that we have reservoirs of mindfulness and discipline deeper than our peers’. And so we try to write fiction, though certainly we don’t need to, and, as this book attests, we often don’t especially wantto, even if we greet the task steeled by a perfect cup of coffee, a glass of red wine and a hot bath, or an Eminem song.

Plus, as Stephen Marche wrote in the Timesthis weekend, the reality is that very few of these writers, if any, will succeed. “The majority of books by successful writers are failures,” he writes. “The majority of writers are failures. And then there are the would-be writers, those who have failed to be writers in the first place.” But failure is seldom on the minds of these writers, except insofar as it stands, temporarily, between them and inevitable success. As of now, there are 675 of those would-be writers featured on the Twitter version of Working, and yet a rudimentary search shows that the word failhas been deployed exactly zero times. What prevails instead is a kind of Pollyannaish resilience, which certain sectors of the culture, as Marche explains, have misattributed to Samuel Beckett:

“Fail better,” Samuel Beckett commanded, a phrase that has been taken on by business executives as some kind of ersatz wisdom. They have missed the point completely. Beckett didn’t mean failure-on-the-way-to-delayed-success, which is what the FailCon crowd thinks he meant. To fail better, to fail gracefully and with composure, is so essential because there’s no such thing as success. It’s failure all the way down.

Indeed, if you hope to Fail Better—and if you hold up literature, as a writer or reader, as a form of bettering yourself, warts and all—you risk ensnaring yourself in a paradox that Jonathan Franzen wrote about in 1996, more than a decade before Twitter even existed:

You ask yourself, why am I bothering to write these books? … I can’t stomach any kind of notion that serious fiction is good for us, because I don’t believe that everything that’s wrong with the world has a cure, and even if I did, what business would I, who feel like the sick one, have in offering it? It’s hard to consider literature a medicine, in any case, when reading it serves mainly to deepen your depressing estrangement from the mainstream; sooner or later the therapeutically minded reader will end up fingering reading itself as the sickness.

And so Working on My Novelis a brilliant litmus test—there are those who will read it as a paean to the fortitude of the creative spirit, and those who will read it as a confirmation of the novel’s increasing impotence. A form that should provide a “radical critique of the therapeutic society,” as Franzen writes, has instead been co-opted by that society. It’s failing better than the best Fail Better adherent could hope.

Search

Categories

Latest Posts

Now you can register to vote at 'Hamilton'

2025-06-26 18:20The giant inflatable duck apocalypse has finally come to Scotland

2025-06-26 17:44Popular Posts

Your 'wrong person' texts may be linked to Myanmar warlord

2025-06-26 19:313 facts and 1 big question about Jupiter's icy moon Europa

2025-06-26 19:12'Hearthstone' guide: How to overrun opponents with a Zoolock deck

2025-06-26 18:42Why it's so damn hard to get a jet black iPhone 7 and 7 Plus

2025-06-26 18:05Featured Posts

Adele on Brangelina: 'I couldn't give a f*cking sh*t'

2025-06-26 17:49Adele on Brangelina: 'I couldn't give a f*cking sh*t'

2025-06-26 17:45Amazon Spring Sale 2025: Best Apple AirPods 4 deal

2025-06-26 16:52Popular Articles

NYT Strands hints, answers for May 2

2025-06-26 19:15Square wants to make your chip card less annoying

2025-06-26 18:50The giant inflatable duck apocalypse has finally come to Scotland

2025-06-26 18:38Lupita Nyong'o unveils her rap alter ego to her Instagram fans

2025-06-26 18:23New MIT report reveals energy costs of AI tools like ChatGPT

2025-06-26 17:30Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest updates.

Comments (26829)

Opportunity Information Network

Who is SpaceX's first moon passenger, Yusaku Maezawa?

2025-06-26 19:32Ignition Information Network

Louis Theroux casually compares Donald Trump to Brexit

2025-06-26 19:25Sharing Information Network

Daisy Ridley reveals exactly why she quit Instagram

2025-06-26 18:13Dream Information Network

In ballots we trust: E

2025-06-26 17:13Inspiration Information Network

Hidden Siri Commands and Unusual Responses

2025-06-26 17:10